February 14, 2024

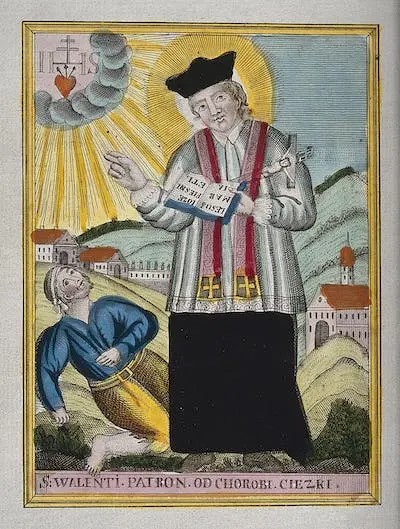

Wellcome Images, CC BY

Last February 14th I mentioned about how Valentine’s Day has become the third most expensive holiday in the US, with Americans spending US$26 billion, or an average of US$192.80 per person. This spending comes from the exchange of cards, flowers, candy, and lavish gifts in the name of St. Valentine. While Melissa and I try not to go overboard, I cannot resist giving her the card, flowers, and candy expected of a dutiful beau. While we tend not to dine out due to the crowds and expense, I do like to cook a good meal for us to enjoy together. American excess was clear yesterday when I went to the market for the ingredients of tonight’s meal. The regular flower section had expanded with bouquets scattered around the front of the store and an entire aisle of fresh cut flowers and red boxes of candy replacing the cookies and sweets that had been there the week before. While love and romance may be at the heart of our modern celebration, St. Valentine was no patron of love.

When I went online, I found St. Valentine’s Day originated as a liturgical feast to celebrate the beheading of not one but several Christian martyrs who died on February 14th. Information on the martyred Saints was compiled by an order of Belgian monks who spent three centuries collecting evidence for the lives of saints from manuscript archives around the known world. The monks were called Bollandists after Jean Bolland, a Jesuit scholar who began publishing the massive 68-folio volumes of “Acta Sanctorum” (“Lives of the Saints”) beginning in 1643. Successive generations of monks continued the work until the last volume was published in 1940. The Brothers dug up every scrap of information about every saint on the liturgical calendar and printed the texts arranged according to the saint’s feast day. The volume encompassing February 14th contains the stories of a handful of “Valentini,” including the earliest three of whom died in the third century. All that is known of the earliest Valentinus is that he died in Africa, along with 24 soldiers. Sometimes all the monks could find was a name and the day of death.

We know a little more about the other two St. Valentines. A late medieval legend reprinted in the “Acta” was accompanied by a Bollandist critique about its historical value. A Roman priest named Valentinus was arrested during the reign of Emperor Gothicus and put into the custody of an aristocrat named Asterius, who made the mistake of letting the preacher talk. Valentinus told of Christ leading pagans out of the shadow of darkness and into the light of truth and salvation. Asterius told Valentinus if he could cure his foster-daughter of blindness he would convert. He did cure her and the whole family were baptized. When Emperor Gothicus heard the news, he ordered them all to be executed, but only Valentinus was beheaded. The body was buried along the Via Flaminia highway that stretched from Rome to modern Rimini and a chapel was later built over his remains. The third third-century Valentinus was a bishop of Terni in the province of Umbria, Italy, who got into a similar situation by debating a potential convert and afterward healing his son. He was also beheaded on the orders of Emperor Gothicus and his body buried along the Via Flaminia. The Bollandists suggested this may be two different versions of the one legend.

THOUGHTS: Whether he was African, Roman, or Umbrian, none of the St. Valentines seem very romantic. One died along with soldiers and the other two (one?) died along with the family they had miraculously converted. The only common thread was they were all beheaded. That might not sell well on a greeting card. The love connection appeared over 1000 years later when English poet Geoffrey Chaucer (The Canterbury Tales) decreed the February feast of St. Valentinus to the mating of birds and English audiences embraced the idea of February mating. Sometimes it seems easier to reconfigure the facts than to face the truth. Act for all. Change is coming and it starts with you.