March 04, 2024

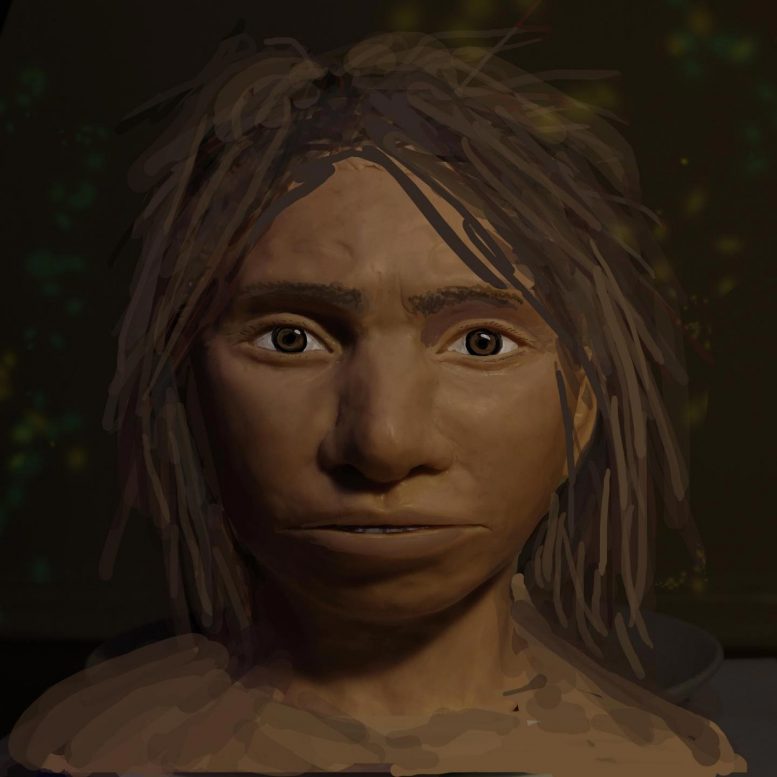

Credit: Maayan Harel

My NY Times feed reported on a lesser known group of humans that split from the Neanderthal line and survived for hundreds of thousands of years before going extinct. While Neanderthals may have vanished 40,000 years ago, they are still a part of our popular culture in museums and TV ads. The humans that split from the Neanderthal line are relatively unknown as few of their bones have been located. Since the first discovery in 2010, the list of fossil remains total half a broken jaw, a finger bone, a skull fragment, three loose teeth, and four chips of bone. What the group lacks in fossils they make up for in DNA. Geneticists have been able to extract bits of genetic material from teeth and bones found in cave dating back 200,000 years, and billions of people on Earth carry Denisovan DNA inherited from interbreeding. The evidence offers a picture of remarkable humans who were able to thrive across thousands of miles and in diverse environments, from chilly Siberia to high-altitude Tibet to woodlands in Laos. This extinct line is called Denisovans.

When I looked online, I found Denisovans (Homo denisova) are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic. The Denisovans get their name from the Denisova Cave in Siberia named after Denis (Dyonisiy), a Russian hermit who lived there in the 18th century and where their remains were first identified. The cave was inspected for fossils in the 1970’s by Russian paleontologist Nikolai Ovodov, who was looking for remains of canids (dogs). Fossils of five distinct Denisovan individuals in the cave were identified through their ancient DNA. These remained the only known specimens until 2019, when a research group led by Fahu Chen described a partial mandible (Xiahe mandible) discovered in 1980 by a Buddhist monk in the Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau. Janet Kelso, paleoanthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, and other researchers offered to search them for DNA. A molar tooth’s (122,700 and 194,400 years old) DNA was distinct enough to suggest it had come from a separate branch of human evolution. The Denisovan fossils date from 200,000 to 50,000 years ago demonstrating the line existed tens of thousands of years, and a 90,000-year-old bone fragment from a Denisovan-Neanderthal hybrid, shows that the two groups interbred.

Other researchers are surveying the Denisovan DNA inherited by living people. The pattern of mutations suggests several genetically distinct Denisovans groups interbred with our ancestors. The most intriguing results have come from studies on people in New Guinea and the Philippines which show signs of repeated instances of interbreeding with Denisovans that were distinct from what occurred on mainland Asia. These findings suggest that Denisovans thrived in vastly different environments. That flexibility stands in sharp contrast to Neanderthals, who adapted to the cold climate of Europe and western Asia but did not expand elsewhere. The Denisovans’ versatility may have helped them last for a long time, and people in New Guinea may have inherited Denisovans DNA from interbreeding as late as 25,000 years ago.

THOUGHTS: After the Denisovans disappeared, certain genes of Denisovans have become more common as they provide an evolutionary advantage in modern humans. Emilis Huerta-Sanchez, a geneticist at Brown University, and her colleagues found a Denisovan gene that helps people survive at high altitudes in Tibet, and DNA from Native Americans carry a Denisovan gene for a mucus protein, though its benefit remains a mystery. Humans are not just related to each other but have genetic links to several hominid kin. Or we can discard genetics and declare our supremacy over others. Act for all. Change is coming and it starts with you.