June 20

In the middle of the back section of my local newspaper was a Reuters article on the discovery of a fungi that can break down the plastic found in landfills. The discovery has launched a startup in Austin, Texas, which will sell disposable diapers paired with the fungi intended to break down the plastic. Tero Isokauppila co-founded Hiro Technologies which now sells online “diaper bundles”. Three sealed jars at the company’s lab show the stages of decomposition of the treated diaper overtime. By 9 months the product appears as black soil. The diapers the fungus attacks contribute significantly to landfill waste. The Environmental Protection Agency says an estimated 4 million tons (907,000 metric tonnes) of diapers were disposed of in the US in 2018 with no significant recycling or composting. It takes 100’s of years for the diapers to break down naturally. Each of the Myco-Digestible Diapers comes with a packet of Pestalotiopsis microspore fungi which is added to the dirty diaper before it is thrown into the trash.

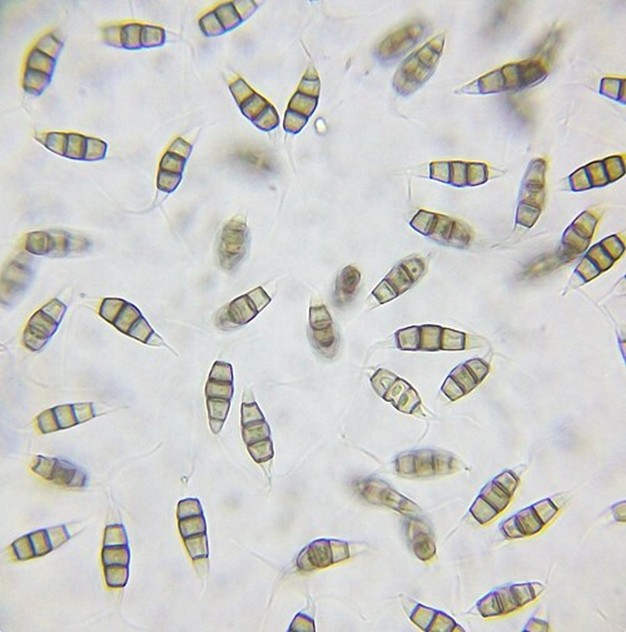

When I went online, I found Pestalotiopsis microspora is a species that lives within a plant for at least part of its life cycle without causing apparent disease (endophytic). The fungus can break down and digest polyurethane (plastics). Pestalotiopsis was originally described from Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1880 in the fallen foliage of common ivy (Hedera helix) by mycologist Carlo Luigi Spegazzini, who named it. Pestalotiopsis also causes leaf spot in Hypericum ‘Hidcote’ (Hypericum patulum) shrubs in Japan. The species polyurethane degradation activity was only discovered in the 2010’s in two distinct strains isolated from plant stems in the Yasuni National Forest within the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest. This was a discovery by a group of student researchers led by molecular biochemistry professor Scott Strobel as part of Yale’s annual Rainforest Expedition and Laboratory. It is the first fungus species found to be able to subsist on polyurethane in low oxygen (anaerobic) conditions making the fungus a potential candidate for bioremediation projects involving large quantities of plastic.

The Pestalotiopsis fungi evolved to break down the lignin compound found in trees. Isokauppila said the carbon backbone of the compound is very similar to the backbone of plastics. Lignin is a class of complex organic polymers that form key structural materials in the support tissues of most plants. Lignin is particularly important in the formation of cell walls, especially in wood and bark, because it lends rigidity and does not rot easily. Most fungal lignin degradation involves secreted peroxidases. Fungal laccases are also secreted, which aid degradation of phenolic lignin-derived compounds. An important aspect of fungal lignin degradation is the activity of accessory enzymes to produce the hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) required for the function of lignin peroxidase. More research is required to see how Pestalotiopsis will decompose in real world conditions. That data should enable the company to make a “consumer-facing claim” by next year. Hiro Technologies plans to experiment with the plastic eating fungi on adult diapers, feminine care products, and other items.

THOUGHTS: When my son was born the reaction of Pestalotiopsis on plastics was unknown. I decided to avoid the waste of disposables by using cloth diapers. While his mom agreed, it was my job to take care of the mess and cleaning required by the diaper pail. There has been a resurgence of interest in cloth diapers recently among environmentally and financially conscious new parents. While disposable diapers remain popular, a growing number of families are choosing to use cloth diapers. This shift is driven by environmental concerns, cost savings, and improved cloth diaper designs. The cost of the fungi diaper packs is not cheap (neither are the disposables), but it could make a significant difference environmentally. Act for all. Change is coming and it starts with you.